The Morning After

What does Trump’s swift win mean for us all? Four possible big-picture implications

Oof.

As the Dispatch writers put it, “Of all the various contingency plans we had in place, ‘landslide in which we know the results within hours and no one contests them’ was probably the election scenario for which we were least prepared.”

Based on: polls and other indications that this would be a very close race; recent history’s trend toward a closely divided country, and toward lawyerizing everything in general; and more specifically Trump and his fans’ history of not conceding elections they lost, and specifically signaling that they planned to cry foul and refuse to concede this one—

for all those reasons, it seemed reasonable to guess that we would not know the winner of the election on the night of, or the day after, and that Trump would contest his loss for days and years to come.

Relatedly, the number-one reason it was so important to me (and to many like-minded Dispatch-types across America) to defeat Trump, was his betrayal of the Constitution he swore an oath to uphold: his and his fans’ sometimes embrace of violence—as opposed to humble, peaceful, orderly transitions of power, respecting the choices of the people.

Accordingly, conversely:

(1) In some ways, the country is actually better off because Trump won—even, specifically, with respect to peaceful transfers of power; and reinforcing republican and democratic norms.

For now (stay tuned and see, four years from now...), we don’t have to rack up any further black marks against our record, as a country, in violence or false allegations of fraud or other attempts to subvert the system. Trump and his fans will have no need of reality-disconnected conspiracy theories, because they actually won, and we will concede they did, fair and square.

In other words, it’s better that they won, because they would have been terrible losers, and we won’t.

Relatedly:

(2) We can set a better example.

We can show them how it’s done, how to lose gracefully—both because we respect the Constitution (and can model how to do that), and because politics isn’t our whole life and identity—at least we Christians, among Harris’s supporters, can model (with God’s help) how to be rooted in something beyond this election, beyond this country, beyond this world, and accordingly not to let dismay over the loss be all-consuming or to turn our whole lives upside down.

Maybe they’ll even watch or listen or learn a little bit.

In other words, in some ways it’s better that we lost, because we can be the more generous, and give them the room they need to play out their delusions until they run out of steam on their own. Better, perhaps, for their psychosis to grow old and die on its own than to be directly opposed in a violent confrontation. I can imagine some reasons that God might have preferred it this way, giving us more opportunity to practice generosity and non-idolatry, and giving them more opportunity to calm down and learn.

Relatedly:

(3) Nature can still heal. It may just take more time.

I would have preferred for this to be the turning point, when we started to repair the damage done to our republic and democratic norms by Trump. On the other hand, even with his victory yesterday, his loss in 2020 can still be seen as the first such turning point; meanwhile even if he had lost in 2024 as well, our record as a country would still not be unblemished: January 6th can fade with time, and can be corrected for, but it can never actually be undone or not have happened.

So, given that such questions are necessarily a matter of degree, all is not lost, nor was perfection ever on the menu. Trump can still leave office voluntarily in four years (less likely), or die of old age and natural causes between now and then (still not likely, but more likely than the former). Even if he holds on through 2028—unconstitutionally, one way or another—someday he will be dead, and the country can begin to move on.

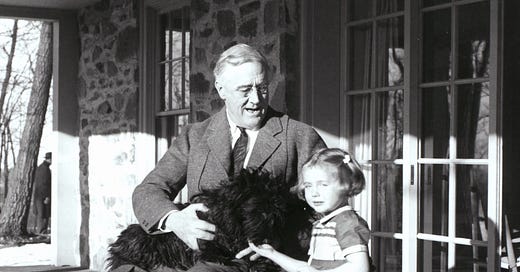

The model here would be FDR. Like Trump, he dishonorably held on to power in violation of our norms and republican traditions, in his case being the first president to violate the Cincinnatian tradition established by George Washington, which then remained unbroken for a century and a half, of voluntarily stepping away from power after no more than two terms as president—and, as with Trump, FDR’s gross cult of personality, among a huge number of Americans, enabled and ratified those violations.

In effect, FDR got himself elected president-for-life, better befitting a third-world dictatorship or perhaps Latin American “strongman” state than a democratic republic.

But, also like Trump, FDR was mortal, destined to die someday. Eventually—the better part of a decade after he did—America was able to move on sufficiently, to make changes (in his case, the 22nd Amendment), to prevent anyone quite like him from ever happening again.

So with Trump. While his fans (for now) are stubbornly loyal to him personally, they are not nearly so attached to anti-republican principles per se; sooner or later, after Trump is gone, many of them may be happy to join with the rest of us in trying to make sure no one else (they may well think, rightly enough, no overweening Democrat next...) ever again has access to the kind of power he did.

What exactly such reforms might look like would remain to be worked out. In the meantime:

(4) Abortion, and the New Wokery Jiggery-pokery, lost.

Elections are funny things. We’re all asked to choose just one of two names, but different voters are potentially voting on a multitude of different issues. I (and that whole Dispatch movement) thought the first-order concern was and should have been the Constitution, the perdurance of our republic, and were voting against Trump because he betrayed the Constitution: We wanted this election to say forcefully that we’re still a country that believes in peaceful transfers of power and respecting the will of the people. Others, however, could equally reasonably think of it in different terms: for example, that this election says that we’re still a country where there’s such a thing as men and women: that while at this point we may not be exactly a Catholic nation or a Christian nation or a conservative nation, we’re at least fundamentally not anti-reality, not anti-humanity. And while Harris tried to some extent not to run as the transgenderism candidate, she and her campaign did try to make the election all about abortion. On their own terms, then, to the extent they did, the American people voted against abortion—even as they also, in Florida (as the progressive news media admitted last night), defeated abortion in a voter referendum for the first time since the overturning of Roe vs. Wade, while also (Nebraska) voting against abortion elsewhere.

Bottom line, America was never going to last forever, and we should perhaps all renew our orientation to first things and more lasting things. At the same time, this election, by itself, was never going to spell the end of America, no matter who won. In democratic politics, “There is no such thing as a lost cause, because there is no such thing as a gained cause”—all decisions are always partial and provisional, always subject to further national conversation.

Back to work!