Mufasa movie review: Disney animated musical is fine, except for the animation and the music...

It takes a perverse genius to let “photorealistic” computer animation wipe out the advantages of the old Disney animated movies, but then also throw away the advantages of “realism” as well

When I first heard this song, I thought, Hey, maybe this new Mufasa prequel is actually going to be good.

The song is impossibly catchy; it has been the #1 favorite of both my wife and our son for weeks. We’ve listened to it over and over and over again, the soundtrack of seemingly every day in our house and every car trip.

It seemed like a worthy successor to the “Just Can’t Wait to be King” song from the original Lion King: equaling or excelling it in childlike irrepressible exuberance, while also both adding more emotional depth (the importance of the relationship between two brothers is an under-explored theme for popular culture), and also containing more philosophical depth than the original—admittedly a low bar, but for a children’s movie, this is practically King Canute contemplating the limits of imperial power, really thoughtful and interesting:

MUFASA: You see that tree

Those birds are watching the world unfoldTAKA: The world unfold

MUFASA: Oh, brother

TAKA: My brother

When I’m king, they will do as they’re toldMUFASA: You may look down on them, but they are free

TAKA: You can’t catch me

MUFASA: And where they go cannot be controlled

TAKA: No one looks down on me

MUFASA: They look down on us, brother

TAKA: Ha!

MUFASA: Some things you chase but you cannot hold

The song—did it go without saying?—is the latest hit in a long series of masterful work by Lin-Manuel Miranda. In general, I agree with Ross Douthat, who observed that “The guy who wrote Hamilton is really good at writing songs, and if you hire him to write your Disney movie’s soundtrack,” then whatever other weaknesses the movie may have, you will end up with a movie whose songs are by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

So after hearing the song perhaps hundreds of times, when we finally saw the movie, I expected Mufasa to be—if not as great as the true high points of the Disney little Renaissance of the 1990s, then at least a worthy successor to the lesser 1990s movie that was the original Lion King.

Alas, even these modestly high hopes were disappointed.

The bad

You know how some trailers trick you into seeing the whole movie, because the trailer was really good, but then when you watch the movie, you realize that almost all of the good parts were in the trailer, and the rest of the movie is mostly filler?

Two big structural problems hobble Mufasa from beginning to end, inevitably marbled throughout: the music and the animation.

(For a Disney animated musical, what else is there? Other than that, it was fine...)

First, recall again Ross Douthat’s observation on the occasion of a previous weak Disney movie, saved (more or less) by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s music: Even if the rest of the movie is dull, at least Lin-Manuel Miranda’s melodies and lyrics will sparkle.

Except when they don’t. While the “Always Wanted a Brother” song and a couple of others really shine, the quality of the other songs is—uneven.

As I listened to one of the songs early on in the movie, I thought, You can tell it’s Miranda, there is some of his signature cleverness, but at the point at which he’s having even a villain laugh off the massacre (tribal genocide?) he’s about to commit with a trivial “bye-bye”, he’s lost the thread, the movie is really missing something. As we watched the rest of the movie, I had the growing sense that Miranda was really just mailing it in—I imagined him feeling, either I’m so good at this, or possibly This project matters so little to me, that: I can just throw together n’importe quoi in a couple of days, they’ll pay me, it’ll be good enough for some dumb children’s movie, and we’ll all move on to the next job.

Maybe that’s unfair to him. Listen and decide for yourself. I think it’s clear that most of the songs were forgettable and the movie would have been better off just that much shorter,* without them.

* At almost exactly two hours, the movie is not an intrinsically unreasonable length, but (like a day wasted at public school): For the quality and amount of content contained, it was unjustifiably long.

The ugly

The other problem is the animation. I had the advantage (or disadvantage) of listening to the “Always Wanted a Brother” song on the car speakers, with no visuals, over and over again; I just assumed I should picture something more or less like “Just Can’t Wait to be King”, but more so.

The more fool I. Of course I should have known that the trend these days (at least for Disney) is “live-action remakes” and “photorealistic computer animation”; I never saw the unnecessary 2019 remake of the (relatively good, original) 1994 Lion King, but Deacon Steven Greydanus’s comments apply just as well to Mufasa, and are worth revisiting at length:

It’s not hard to see why the Favreau nouveau Lion King pales in comparison to the original hand-drawn tale of a young lion cub who loses his father and his way before rising up to reclaim the throne. (I’ve always found the original underwhelming,

It is!

but the remake’s deficiencies are equally inescapable for fans and non-fans.) . . .

. . . The Lion King’s photorealistic animals . . . can’t remotely match the emotional expressiveness of their hand-drawn counterparts. Their faces are nearly as inscrutable as the subjects of a wildlife documentary. The hand-drawn Pumbaa might have been ugly, but his body was mostly face, and Ernie Sabella’s boisterous vocal performance flowed into every stroke of his rendering. Seth Rogen is fine in the role, but few viewers will feel the same emotional connection to a photorealistic warthog. . . .

When Zazu bows, wings spread, before Mufasa in the “Circle of Life” opening number, the original gives us a reaction shot of the regal beast gracing Zazu, amid the solemnity of the moment, with a beneficent smile and a nod of acknowledgement. In the remake, after the same bow (a movement glaringly at odds with Favreau’s general preference for naturalism) comes the same reaction shot — except the photorealistic Mufasa can’t react: can’t smile or even nod his head in that gracious way. He just has resting lion face. Even if you’ve never seen the original, the recreated “reaction” shot has no purpose, except to illustrate the emotional limitations of photorealism compared to hand-drawn animation.

The movie makers may well have added some slight touches of expressiveness here and there, at the margins, in Mufasa compared to the 2019 Lion King, in response to just such a critique. But overall, the same (incredibly strong) criticisms still hold true.

In other words, Disney either learned essentially nothing from the weaknesses of the final product itself, or the feedback from audiences and reviewers (like Greydanus)—it was six years ago; Disney has had plenty of time to learn, and to adjust accordingly—or else doesn’t care, or considers the tradeoffs worth it.

(What tradeoffs, exactly? Mainly just the profitability of a naked cash grab, I assume.)

Don’t take our word for it; see for yourself, do your own side-by-side comparison:

(From the good/1994 Lion King:)

(From Mufasa:)

I think this obsession with “realism”, where the (deceptively) simple beauty and artistry of the Disney animation of an earlier era would have worked much better, hobbles the movie throughout. (I don’t doubt that the old Disney cartooning took a hundred times as much work as it looked like—they made it look easy—but it’s not as though creating computer graphics at this level of detail isn’t incredibly labor-intensive, too. In other words, Disney is choosing this, this is not some necessity thrust upon them.)

My wife and I kept having to ask each other, as we tried to keep up: Which character is this? Is that Obasi? No, it’s some other identical-looking lion... The movie makers are, I think, clearly aware of this problem, and do their best to compensate, within the limits of this “photorealistic” framework, by color-coding the different “tribes” of lions—Mufasa’s tribe has golden-toned fur, Taka’s is gray, the emperor-conqueror’s tribe is white*—but it only goes so far; they’re still all more or less interchangeable lion-colored lions, especially by the time they’re all covered in snow.

* (though he talks about having intentionally assembled an army—if he has recruited or conscripted from other tribes, why is his army not more variegated-colored? and why do we only ever see him or even hear of him killing off entire tribes, never attempting to enslave any remnant? or if his “army” is only from his own genetically related pride, then how did his tribe get so much bigger or stronger than others’?)

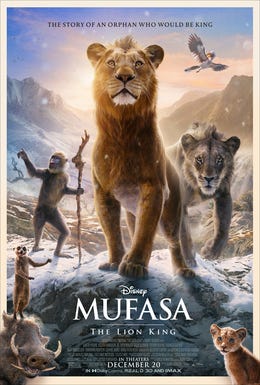

The “realism” hobbles the movie throughout, but it hurts the movie worse in some places than in others. In this movie poster—i.e., not just how the characters appear for much of the movie (though they do), but also what Disney has selected as an ideal representation, standing in for the whole movie—Mufasa has a pitiful half-grown mane:

(In human terms, as a friend has said of some teenagers, he doesn’t have a beard, he can’t grow a beard yet, only a “hairy face”...)

I get that it’s supposed to show (“realistically”) that he is a youth, not yet a fully grown elder of the community, but it makes him look as though he has the mange.* Disney tries to compensate by stretching his neck way out, but it doesn’t compensate and make him look majestic; it just makes him look like a llama with the mange. Or maybe a Lewis Carroll epileptic-dream illustration.

—with the mange.

* (In the original Lion King, by the end of the coming-of-age montage, Simba was depicted as having a beautiful fully grown mane, notwithstanding that his character very much still had some growing up to do.

)

I’m not sure which is worse. In this thumbnail that Disney has selected as an ideal representation, standing in for the whole movie on their streaming service, you can see that Timon has been transformed from the witty wise guy of the original movie, into something more like a weasel with scary-clown/sociopathic-murderer-Joker makeup:

This is perhaps part of why the movie seems determined to compound some of the problems already produced by this switch from cartoons to taxidermy—the faces are less expressive; you feel as if you were watching a bunch of unrelated animals walking around, while listening to actors doing an unrelated script reading—by keeping the shots wide, not giving characters like Pumbaa and Timon the close-ups on their faces that might enable you to see some hint of facial expression or movement. At one point, Timon jokes that the civet in the previous scene got more screen time than Timon and Pumbaa do.

Awkwardly, this comment spotlights one more big structural problem with the movie, inviting us really to stop and meditate on it, because the civet was never even seen on screen, but in a brief blink-and-you-missed-it distance shot: Think back to the nature documentaries that, at some level, this movie’s style is derived from. What was appealing or interesting about them?

(Ignore the fact that, when you first start watching this “photorealistic” movie, you are acutely aware that the animals on the screen are not real, that they have just the wrong “uncanny valley” combination of too much realism for animation, just a little too much human expression added to the faces for them to be real animals, just a little too little convincing artistry in the articulation of the joints and the fluidity with which large cats move in the real world; that you can’t escape the impression that either you are watching soulless robots doing their horrifying best impression of real animals, or else you are watching dead and taxidermied animals grotesquely reanimated, paraded around like macabre puppets. By halfway through the movie, you won’t even notice that any more...)

The attraction of those nature documentaries, the iconic and memorable core, was that eventually, at some point, the cheetah or lion or whatever would pounce, and finally make the kill. It’s even in those lyrics, in the best song at the core of this movie; look again, above: “Our prey may run away, but they can’t hide.”

But this movie is acutely aware that, if all the animals are sentient “talking” animals,* the moral case for even lions to become vegetarians is intuitively very strong.** Thus the movie congratulates Mufasa on using his sense of smell to be a good servant leader for his little band, finding a civet for them to eat in their moment of greatest need, but carefully avoids showing the kill, or the eating, or even (almost at all) the prey while alive, lest we contemplate its mortality, and its moral worth as (in effect) a person, as all the animals in the movie are.

* (In the Chronicles of Narnia, everyone could eat non-talking animals as freely as in our world; but when some characters discovered that they had unknowingly eaten talking animals, served to them when they were guests at dinner, they considered it a grave moral crime, equivalent to cannibalism.)

**:

Similarly, we see none of the brave (and inexplicable, suicidal—why didn’t they run away, if they were so sure they would all be killed?) last stand that Obasi’s tribe makes before the conquering army, almost none of the (theoretically stirring) turning of the battle at the end when the other animals are all rallied to repel the invading army together; we see almost no action at all until the final fight scene between (mostly) Mufasa and the emperor-conqueror.

(Even then, one is tempted to quote the irreverent movie reviewer from another Internet era (warning for language and content): The director here has accomplished the impossible, he has managed to make even the fight scenes boring.)

What is left, then, is about two hours of dialogue, that happens to have slow-moving, queasily almost-realistic animals walking around in the background during the line readings. The movie makers have deprived themselves of the one source of action and interest where their nature-documentary style might really have had something to offer.

Even more fatal for the film, however, is that other side of the coin, the moral dimension, where the same problem is repeated at another level: The movie ends up being just the wrong combination of too concerned with realism in some ways, not enough in other ways, the worst of all worlds. In the climactic moment, in which Mufasa and his lion friends are trying to talk the other animals into joining the fight and banding together against the white lion army, you can’t help wondering: Why should they? So that this lion can eat them later, instead of that lion? Mufasa and his friends try to make some kind of an argument that the emperor-conqueror violates the larger “circle of life”, but the argument is as short on specifics and rational sense as it is on emotional resonance. The other animals shrug and agree to join the fight anyway, but it still doesn’t make any sense when they do. The human (or AI?) authors of the story might as well have written, Here’s where the stirring speech would go, we’ll fill in the details later.

Indeed, at the point at which Mufasa is declaiming that no lion is as strong as “an oxen” (it really grates on the ear—“oxen” is plural, it’s the equivalent of saying no lion is as strong as “an elephants”), you wonder whether what you’re hearing is someone’s vague idea of what a stirring speech might sound like, if you could find someone with any skill to write one. You wonder whether AI could have done a more passable job, given that goal—or, perhaps, whether this part of the script was written by AI, and that’s the problem.

Probably not, but it would explain some of the movie’s other problems, too. The general story overall works well enough, but it relies heavily on the potentialities (for emotional stakes, for character development, for setting up the next steps) created by taking a character away from his home and his people, with or without a hope of eventually getting back to some kind of home. Possibly some human (or AI?) author looked at the original Lion King and figured, Hey, it worked there; let’s reproduce what works. By the third time that you’re seeing this fish-out-of-water/hero’s-journey cycle starting with a third character in this one movie, it feels a lot like when you first realized that every Star Wars sequel was going to have to have someone blow up another Death Star.

What’s left? Arguably the much more important aspects of the movie are the characters and the story. Maybe a better movie review would have started there. Or maybe just a better movie—with less glaring, fatally bad structural weaknesses throughout—would have allowed starting there.

The good

Credit where due: I think the characters of Mufasa, Taka, and Sarabi just about work, along with the love story between Mufasa and Sarabi, the related reason (as well as the other reasons given) for Taka to turn against him, and the relationship between the two brothers in earlier, better times, leading up to that turn.

I think the way Mufasa’s humility, in seeking the good of others rather than his own, is rewarded, first with the love interest, then with being crowned king, just about works.

But again, it’s also the worst combination of too “realistic”, and not realistic enough. In a real world with real animals, why should the lion be “king” over other animals? Why should anyone be a king of any kind?

Or if this is a human story with human characters, why are they subject to so many of the limitations of animals?

In a realistic world with real animals, why would the emperor-conqueror be motivated to kill off other lions’ tribes? (In effect, he and his whole people are Obasi’s unexamined prejudices against imagined larger, stronger, uncivilized outsiders, made flesh, but with no explanation of how or why that was possible.*) If he’s expanding his territory, why would he be motivated to go, with his whole army, many territories away, in pursuit of just one lion (or three) that survived his previous massacres? or if he is so motivated (out of a desire for vengeance, on the one who killed his son), why can’t other prides or other animals take advantage of his entire army’s long absence from their own territory?

(*)

We are given the fascinating suggestion, only in passing, that he has adopted a stronger role as king in his own pride, whereas other prides’ males, like Obasi, are traditionally content to lie back and let the women do the heavy lifting, including the killing. It seems like an opportunity to explore feminism, renewed masculinism, or other fascinating possibilities, actually engaging with interesting ideas.

Unfortunately, like other opportunities, the movie missed this one.

Edit: corrected subject-verb agreement, "they don't" for "it doesn't".